Not long after we met, Martin and I went out to eat at an Ethiopian restaurant in my old San Jose neighborhood. I'm not going to name names, because I don't have nice things to say and that was 15 years ago … so for all I know things have changed there. I don't want to give the place a bad rap based on a 15 year old memory.

It was not a good memory, though. The food was gritty. I can't think what may have caused this, maybe the spices were very coarsely ground or just added too late in the cooking process, but whatever the reason it was like eating sand. But the main thing I disliked about my Ethiopian restaurant experience was what I forever remembered as "that bread." It was both spongy and gelatinous all at the same time. It was wet and tasteless. It was inedible.

So I felt dread when I began to plan my Ethiopian menu. Because every single recipe said "serve with injera," which it turns out is the proper name for "that bread." But you know, I try to do things the right way, so I resolved to make "that bread."

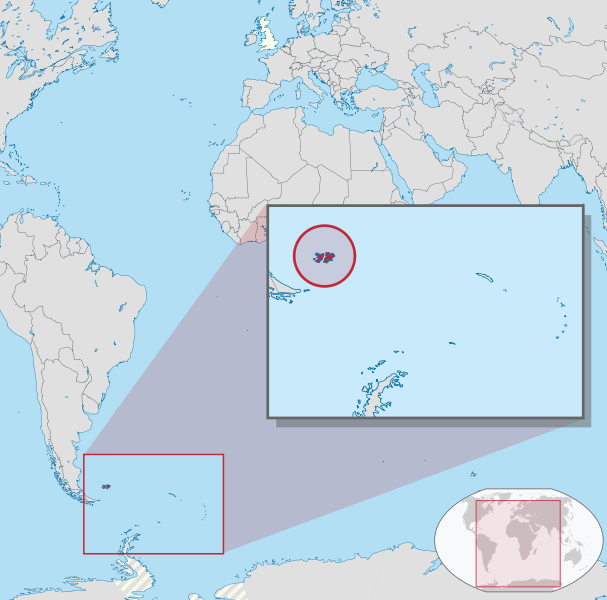

First a little bit about Ethiopia. With 86,000,000 inhabitants, it is the most populous landlocked country in the world. It is also the cradle of humanity—Homo sapiens emerged there 400,000 years ago and from there migrated to the Middle East and beyond. Ethiopia has a long history stretching back to the 2nd millennium BC, and was once—many centuries ago—one of the world's great powers.

.svg/550px-Ethiopia_(Africa_orthographic_projection).svg.png) |

|

If you grew up in the 80s, as I did, you probably remember Ethiopia as a place of famine. Between 1984 and 1985, about 8 million people in Ethiopia were under threat of starvation, and 1 million of those people actually died. Fortunately, Ethiopia has recovered from those dark times, and it is now the largest economy by GDP in central and eastern Africa. It still has some problems, though, not the least of which is its system of marriage: marriage by abduction is by far the most popular form of courtship and engagement in the country, with up to 92% of marriages beginning this way in some parts of the nation.

Traditional Ethiopian cuisine centers around "wat," a thick, spicy stew made from either meat or vegetables and served with injera, otherwise known as "that bread." So it actually wasn't too hard to pick this menu though I'm afraid I chose the easy way out with this recipe:

Doro Wat

(this particular version came from

EthiopianSpices.com, a company that sells imported Ethiopian spices)

- 5-8 pounds of chicken drumsticks and thighs, skin removed

- 8 large onions, chopped fine

- 2 cups vegetable oil

- 5 tsp minced garlic

- 2 tsp minced ginger

- 1/2 cup berbere

- 1/4 cup paprika

- 2 tsp black cardamom

- 2 tsp wot kimem

- 2 tsp salt, or to taste

- 1-3 cup water

Why was this the easy way out? Because doro wat is Ethiopia's national dish, so it was the obvious choice. I picked it more because it sounded good than anything, though.

Here's the recipe for the

wat kimem (a spice blend):

(From Celtnet.com)

Yes, this is all weird stuff that you will have to special order.

I also chose a lentil dish:

Missir Wat

(from

The Berbere Diaries)

- 3 onions, chopped

- 1/2 cup oil

- 2-3 tbsp. berbere

- 7 oz canned, diced tomatoes

- 3 cups water (more if needed)

- 2 cups split red lentils, rinsed

- 1 tbsp ginger, minced

- 1 tbsp garlic, minced

- salt to taste

And yes, "that bread:"

Injera

- 2 cups teff flour

- 2 cups water (more if needed)

- 1 tbsp active dry yeast (if needed)

OK I have about a million different things to say about this injera recipe. First of all, it took me forever to settle on one. The Internet is full of people talking about different/the best ways to make injera. There are a lot of different opinions and techniques, and lots of problems. I read many forum posts complaining about injera's tendency to stick to the pan, so I zeroed in on a recipe that had quite a few success stories attached to it. It also turned out to be the simplest of the recipes I found. It came from a forum post on The Fresh Loaf.

Second, you don't have to use teff flour if you can't find it. I got mine at the co-op in Grass Valley, so if I can get it out here in Hodunk Hippieland you can probably find it, too. But if you can't, don't go out of your way. Teff isn't used exclusively for injera even in Ethiopa, because it grows only in middle elevations and places that have decent rainfall, which means it's expensive for most of the people living in Ethiopia. For this reason wheat, barley, corn or rice flour is often used instead of teff. I've seen a lot of recipes that just use all-purpose flour, and some that use barley or finely-ground corn flour.

So I'm going to start this entry with the injera, because you have to start making it a couple of days before meal day.

Now I've tried to make sourdough starter at home and have had absolutely zero luck, so I didn't have a whole lot of faith in the whole injera fermentation process. But here's what you are supposed to do:

Three days before meal day, mix the teff with the water and put a dry clean towel over the bowl. Let it stand until it starts to smell sour and get a little bit bubbly. That means it has fermented correctly.

Surprisingly, when I did this my teff mixture did actually look and smell the way it was supposed to 48 hours later. Except for the large spots of green mold on top. So I poured mine away and did it again, but I was only able to let it sit for a day. It didn't smell very sour or look very bubbly at the end of that 24 hours, so as I started to prepare my meal I added a tablespoon of active dry yeast to help the mixture rise while cooking. (Disclaimer: the recipe I used said to use 1/2 cup of a sourdough starter, which I did not have, but you would get a truer sour flavor in your bread if you did this. Ideally, though, you would not get any mold in your batter and you would not need to use any kind of leavening agent at all.)

You may need to add some water after your teff batter has been sitting out for a while. It should not be thick, but should resemble the batter you would use for making crepes. Add enough lukewarm water to get it to this thin consistency and then add yeast, if using.

Heat a high-quality nonstick pan and spray it with a plain-oil cooking spray just in case. Pour the batter into the pan and swirl it around until it covers the entire bottom of the pan, just as you would if you were making a crepe.

Wait until you see bubbles come to the surface, about 1 or 2 minutes later (just like making pancakes). Now cover the pan and let the injera steam for another 2 or 3 minutes. Do not flip it over! Just slide it from the pan when the top is firm.

Of course you want to do the actual cooking of the injera towards the end, after your other two dishes are finished. Here's how to make the rest of the meal:

First make the wot kimem—just put all the spices together in a grinder or mortar and pestle and process until fine.

Now, when you are done making the wot kimem you will note that it does not smell like anything you would actually want to eat. It smells like how I would imagine an old-timey apothecary would smell. Like chemicals. I was almost afraid to put it in my food, but as they say at my kids' charter school, I persevered. On to the doro wat:

In a large pot, heat the oil over a medium flame and add the onion, garlic and ginger. Cook, stirring, until the onions start to brown. Now add the berbere and the paprika and turn the heat down to low. Simmer for 15 to 20 minutes, stirring frequently. Add a little bit of water as necessary to prevent sticking.

Now add the chicken, stirring to coat. Keep adding water in small amounts—you want the sauce to stay pretty thick.

When the chicken is fully cooked (175 degrees for thighs and drumsticks), add the salt, black cardamom (which also smells like medicine) and the wot kimem. Let it simmer for a few more minutes to incorporate the flavors, then serve.

Meanwhile, make the lentils. Red lentils don't have to be soaked so this dish comes together pretty quickly.

In a large pot, heat the oil over a medium flame and then cook the onions until they are translucent. Add the berbere and let simmer for five minutes or so. Add the tomatoes with a few spoonfuls of the juice and stir to combine. The add the water and bring to a boil.

Put the lentils in the pot and mix well, then reduce heat to low. Simmer until the lentils start to soften, adding more water if needed. Now add the ginger and garlic, and continue to simmer until the lentils are tender.

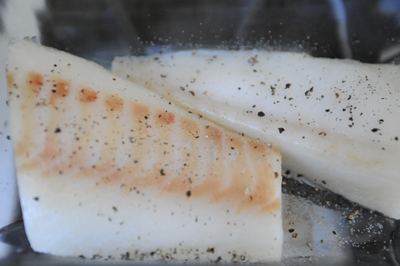

I'm sure you are dying to know if this experience at all resembled that horrible restaurant meal from 15 years ago, and I am happy to report that I am a much better cook than whoever it was that made that particular meal back in San Jose, haha.

I absolutely

loved this meal, and so did Martin, even though the chicken was on the bone which is usually a deal-killer for him. I even loved "that bread." It was nothing like that gelatinous, horrible mess we had back in San Jose. It was spongy, yes, but it was also firm and nutty and tasted wonderful with the other two dishes. I don't know if I got the texture right but I sure did enjoy the results.

Even with the weirdness of the wot kimem, the doro wat was heavenly. Yes, heavenly. I'm glad to say that it was not the gritty schlop of my memory but a rich, delicious stew with a complex blend of flavors. And the missir wat rounded out the meal perfectly. It was flavorful but less complex than the doro wat, which turns out to be exactly what was needed to make this a perfect meal.

My kids of course moaned and complained and ate nothing. But who cares. I'm going to make this again, and often (though I will probably use boneless chicken next time, just to make my husband happy). It was delicious, and definitely lands on my list of my favorite meals of the year, and quite possibly is also one of my top five meals in TbS history. I am really glad that my blog led me back to Ethiopia after that awful experience in San Jose, because I doubt otherwise that I would have ever tried Ethiopian food again. Now I think it might be one of my favorite cuisines.

Next week: Europa Island

For printable versions of this week's recipes:

.svg/550px-Fiji_(orthographic_projection).svg.png)

.svg/550px-Ethiopia_(Africa_orthographic_projection).svg.png)